The Homologators – Lancia Delta S4 ‘Stradale’

If a manufacturer wants to go racing, they need to build a fast car. But here’s the thing, they can only race a version of what they sell. Back in the '90s, this presented a crafty opportunity. Enter stage-left, the homologation car.

Homologate. It’s from the Greek language and means, roughly, to gain the approval of a higher authority. Get their blessing and you can go and do whatever it is you were seeking permission for. In terms relative to us, that means racing. There are obvious exceptions like Formula One cars and other open-wheeled racers. However, for track-based machines that start life as a road car, there are homologation rules. In short, if a manufacturer wants to race it, they also have to sell it.

These days homologation is a blurry world of endless regulations and rules. Rally cars and touring cars are all homologated, but you wouldn’t know it if you went into a dealership. This is because the manufacturers don’t need to make a song and dance about it. Sell a few Fiestas, or a few BMW 320Si’s and you’re away.

Back in the ‘80s, however, it was a different affair. Motorsport was a roguish, murky world in which teams were more than happy to exploit the weaknesses of a rulebook. And this was never more the case than in 1982 when the FIA introduced Group B. It was supposed to be the category that would unite Group 4 (modified grand touring) and Group 5 (touring prototypes) classes. Instead, it would be the series that would be exploited in the name of extreme power. It would also be the series that would permanently etch itself into the history books for all the wrong reasons.

In order to compete, manufacturers had to homologate a minimum of 200 of whatever car they wanted to use in competition. This was clever on the FIA’s part, as it hoped the need to make road-going versions would cap the abilities of the competition cars. For example, a stock Delta wasn’t a threatening car with its 1.5 litre engine, so the rally version couldn’t possibly be that wild, right? Rally teams, however, didn’t get the memo. Being the cheeky scamps they were at the time, the manufacturers removed some roll cages, threw in some carpets and then sold their race cars to the general public. The rally cars, then, spawned the road cars. Not the other way around, as the FIA had hoped. Cheeky, but completely legit.

On the stages, these cars were absolute pure, unadulterated, wheeled lunacy. Drivers, while heroic, were often quoted as being afraid of the cars. They were uncontrollable wild stallions. Some cars were reportedly putting out 600hp. That’s a ridiculous amount of power in 2019, let alone in 1985. And while the road cars were slightly de-tuned, they were only ever really a few turns of a spanner away from being a rally car. And that brings us to the first car in this new series – the Lancia Delta S4, or Stradale to its friends.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, Lancia was at the top of the rallying world. First there was the Stratos and then, when that lost its competitive edge, their was the mighty 037. But even that, despite being built for Group B, soon lost its footing against its rivals, particularly Audi with its revolutionary four-wheel drive system. Lancia needed to step up its game.

In a bid to keep up with its rivals, Lancia abandoned two-wheel drive and by the early ‘80s it was working on all-wheel drive systems. It produced an all-wheel drive Delta prototype and then ran with the idea. The Delta, it seemed, would be the perfect car to take on Group B. But only after having a few choice modifications.

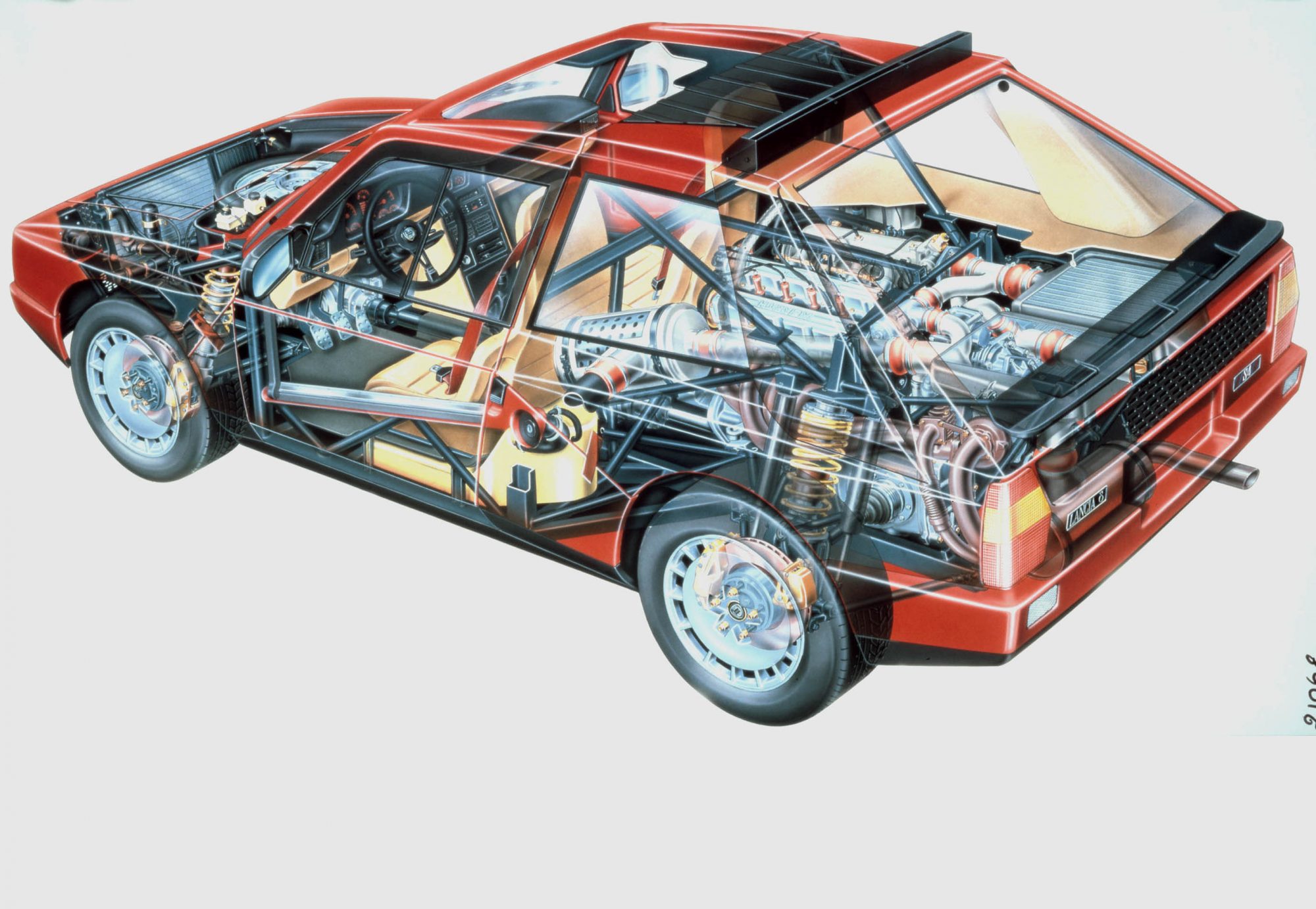

First of all, they binned off the rear doors, making the Delta a three-door car. Then they wedged in the all-wheel drive system, which consisted of an open front differential and a locking rear one, with a centre diff being made responsible for the torque split between front and rear. However, this was way before the days of clever electronic differentials, so instead the maximum power split was fixed and determined by whatever differential the mechanics wedged in (adjustable distribution 25%-75% to 40%-60%). Though the Furguson-derived coupling did distribute said power in relation to which (front or rear) axle was rotating slower. Simple, but effective.

In road-going trim, the ‘normal’ Delta housed a transversely-mounted four-cylinder engine up front. The rally S4 took a different approach. Lancia didn’t want their Group B warrior to be nose heavy, so instead, it put the engine in the middle for better weight distribution and turned it through ninety degrees, too. Oh, and the lunatics at Lancia decided that a turbocharger wasn’t enough, so they bolted a supercharger to it, too. Enter stage left 480hp. Though some Lancia insiders from back in the day will attest to it having 500hp. A believable figure given that under extreme testing the same engine knocked out 1,000hp.

Now, going back to homologation. If Lancia wanted to compete with this new Delta-based car, which by this time had earned the name S4, it would need to build a minimum of 200 for road use. Logic would dictate that they could just homologate the Delta, except they couldn’t. The Delta was wildly different to the S4. In fact, it shared nothing other than a name and a slight, squinting, passing resemblance. Underneath the carbon-composite bodywork, there was no Delta to be found. Instead, there were myriad lengths chrome-molybdenum tubular space-frame with carbon fibre reinforcement, forming a space-frame chassis. This car was built, make no mistake, to be a rally car, not a road car. So how did Lancia get around it? How did they homologate a Group B rally weapon? Well, um, they just homologated a Group B rally weapon. It was a rally car with air con, basically. Not that the air con worked all that well.

Okay, so Lancia did make some changes. The body was made from epoxy and fibreglass rather than being carbon composite, and the space-frame chassis was constructed from more common steel and aluminium, but that was about it. The power was wound down to approximately 250hp, but it was still the same mid-mounted, twin-charged unit. The all-wheel drive system was the same, too. Oh, and in the interests of making it nicer on the road (though we use that word loosely), Lancia threw some suede and alcantara in it, along with a bit of sound deadening, that rubbish aforementioned air conditioning and power steering.

The interior of the rally car…

…and the interior of the road car.

Known colloquially as the Stradale (Italian for ‘road-going’), the homologation S4 was nothing short of a nightmare to live with. The clutch was incredibly hard, the gearbox was stiff, the suspension was less than forgiving, it was loud, it was hot, the air-con didn’t really work, the gearbox was ludicrously loud, the handbrake did nothing and it was deeply uncomfortable. It was also 100,000,000 Lira. And no, that’s not a typo. It was five times more expensive than a ‘normal’ Delta HF Turbo.

Lancia, in order to pass homologation standards, had to build and sell 200 Stradales. That was a lot, or it least it was a lot when it came to a car that really wasn’t that great on the road. So did they build 200? Nobody actually knows. Some say they did, whereas others say they just made it look like like they did by rapidly moving cars around site to confuse the FIA person with the clipboard. Very canny.

The end of the S4’s story is not a good one. It was an S4 in Group B trim that crashed on the Tour de Corse in 1986. Miscalculating a corner, the car’s driver, Henri Toivonen crashed the car into a ravine. The car’s fuel tank, located under co-driver, Sergio Cresto’s, seat ruptured and burst into flames. The crew were killed in the fire and with their tragic passing, the fates of Group B and the S4 were sealed. The competition cars were soon taken off the stages, while the road cars were in for an even less sympathetic fate – there are unconfirmed reports that the unsold ‘Stradale’ S4s were, due to having their fuel tanks in exactly the same place, crushed.

It’s a sad end for the S4, and with it a morbid legacy. But even so, the S4 should be recognised. It was, for all its lunacy and lack of safety, a proper race car for the road. Those who did get their hands on a ‘Stradale’ also got something special, something pure, and something immeasurably close – be that a good or bad thing – to the car that was for a short time, a legend on the rally stages.